Welcome to Will’s World. Before I start this issue, I want to thank everyone who has read, shared or subscribed to date. I have been overjoyed with the positive reception this newsletter has gotten. It now has over 200 subscribers and it is clear that people want more wacky, weird and interesting content in their media diet and I am very happy to provide that for a small group of people. Again, thank you for taking the time to read this. If you have any feedback or ideas you think I should cover please get in touch by replying to this newsletter or DM me on Twitter. If you would like to write for Will’s World, please reach out. I am now considering getting some people to contribute guest posts. Now follow me down the rabbit hole below to learn more about plant consciousness, Japan's simple and effective approach to land zoning and the interesting research that might change our stance on dietary fat.

Are plants conscious?

Most of us consider plants to be very simple organisms. We plant them, they take in water, carbon dioxide, light, they grow and then they die. However, a relatively new field called plant neurobiology has been investigating whether they are more intelligent than we give them credit for. Some researchers in this field have also been asking the question - do plants possess consciousness? A recent article in the New Scientist opened my eyes to the fascinating research being done in this field.

Did you know that if you take a “touch-me-not” plant (mimosa pudica, a type of plant whose leaves close up when you touch them) and put it in a chamber with an anaesthetic and then touch it, its leaves don’t close up? Or that tomato plants can secrete a chemical in the presence of its predator, caterpillars, that causes them to go crazy and cannibalise each other? Or that evening primroses can sense when a pollinator like a bee is nearby by “listening” for specific vibration frequencies so they can then ramp up their production of nectar? Now while these examples are not evidence of consciousness in plants it does show us that plant behaviour is more complex than we think. This behaviour is driven by a rich understanding of their environment. So when does that understanding become so strong and the behaviour so complex that we consider them to exhibit consciousness?

A leading researcher in this field, Professor Paco Calvo, has been studying this question and he has set three criteria for assessing whether the cognitive behaviour displayed by plants can be characterised as complex. Firstly, the behaviour must be dynamic, and flexible rather than a simple “A causes B” response. Secondly, it must be predictive of some future change. And thirdly, it must be directed towards a clear goal. The most interesting experiment of complex plant behaviour I found was a 2016 study by a team of researchers that conditioned a pea plant to grow in the direction of a breeze using light. They placed light in the direction a breeze was blowing and then these plants started growing in the direction of the breeze even in the absence of the light potentially due to their conditioning.

Critics of this research cite the replication failure present in some experiments but this field is still in its infancy and I think this is really important research that we should pay more attention to. If breakthroughs are made in this space it could really challenge our brain-centric model of consciousness because plants (unlike nearly every animal) don’t have a brain. Most of the leading theories of consciousness focus heavily on our neural anatomy and view the brain as a self-contained generator of consciousness but perhaps the brain may not be as pivotal to consciousness as we think. Maybe there are other forces at play. There are some interesting alternative theories of consciousness which focus on our brain’s relationship with things like electromagnetism. Perhaps our study of plant consciousness could lead us to lending more credence to theories like this which are considered “whacky” or “kooky” by mainstream science.

Plant consciousness could also completely upend our relationship with other living things. We typically treat other living things proportional to how conscious we perceive them to be. We seem to have no problem pillaging millions of acres of soil of its biodiversity and health with monocrop agriculture. But would we treat the animals we keep as pets with the same lack of respect? Absolutely not. So if we begin to realise that plants and potentially fungi are more conscious than we think, how does that impact our relationship with them? Is there an alternate reality where being vegan or vegetarian for the sake of animal welfare becomes a bogus reason as we realise that plants are as conscious or nearly as conscious as animals? Now that might be a stretch but it's an interesting thought experiment nonetheless.

How Tokyo Has Kept Rents Low

In the last decade, rents have risen significantly in most large cities across the world. Dublin rent prices have increased by 80% in the last 10 years. Meanwhile last year the average rent in New York City increased by a whopping 33%. One outlier in this global trend of cities with rising rents is Tokyo. Its population is growing at a faster rate than New York and London yet in the last 5 years the average rent there has only increased by 20% compared to a 100% increase in these other cities. Why is this the case? Well, Japanese housing policy is a complex topic and the stability of Tokyo’s housing market can’t be attributed to just one factor. However, the part of their policy that interests me the most is their approach to land zoning (i.e. what buildings can be built on different types of land) because it is so different to the methods used in Ireland, the UK and the US and its clear that its been a key part of Tokyo’s success in keeping rents low1.

Legislated for at a national level instead of locally

In Ireland, the US, the UK and most western countries, the rules that govern land zoning are made at a city or regional level but in Japan they are set at a national level. This makes the Japanese system less prone to NIMBYism2 because if someone wants to change housing policy then they have to make their case to the national government representatives rather than local government ones and this is harder to do. This is good for people who like to keep house prices and rents low.

Simple rules for a complex system

The housing market is a complex system and trying to control the outputs of a complex system with an abundance of overly prescriptive rules is a fool’s game (good article here on this subject). Lots of very specific rules do not lead to success. The Japanese don’t try to complicate their approach to land zoning. Their system is remarkably simple with only 12 categories of land zones as opposed to the hundreds typically seen in the US system. Housing can be built in every single one of these zones. This flexibility allows cities to adapt to meet local needs.

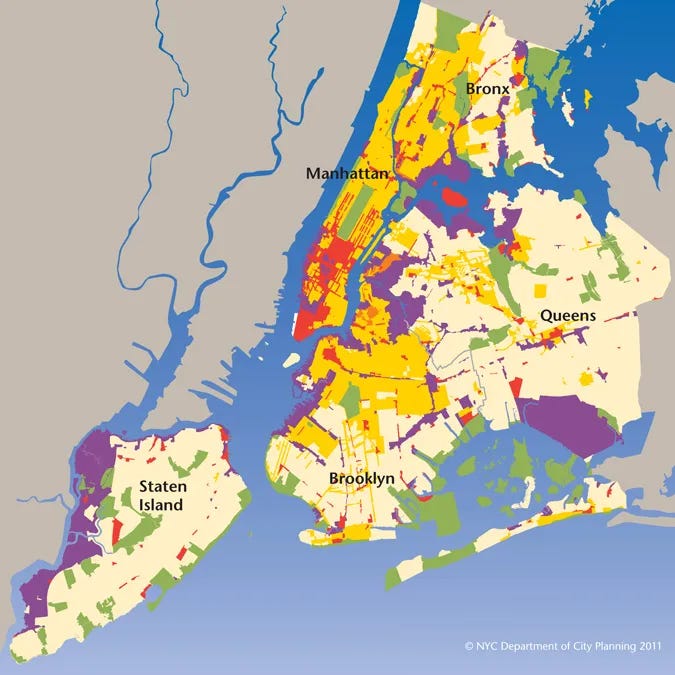

This system is brilliant for enabling mixed-use developments where people can live, work, shop, eat or drink out and access public amenities all within a 15 minute walk, cycle or public transport ride. Due to the prescriptive nature of many western land planning systems this type of urban living can be hard to achieve. For example, the map below shows the zoning plan for New York, America’s most densely populated city. Everything in yellow is zoned for single or two-family residential use. Nothing else is allowed to be built there. This is insane.

In Japan there is no differentiation between different types of residential use e.g. only single-family residential can be built in this zone. They also do not set arbitrary height limits of which those in Ireland are only all too familiar with (see Blackrock’s Local Area Plan or note the absence of high-rise buildings in Dublin for an example of arbitrary height restrictions). The Japanese system is responsive to each site's unique dynamics i.e. if the building is set further back from the street, then you can build higher. The Japanese system also very simply divides cities into an Urbanisation Promotion Area (UPA) and Urbanisation Control Area (UCA). This helps to control urban sprawl by clearly defining where in a city is to be urbanised and where is not.

This very simple land zoning system in tandem with other measures has allowed Tokyo to match housing supply with demand consistently for the last 50 years. Tokyo has had more housing than households every year since 1968. There are definitely lessons that countries like Ireland could take from Japan as we seek to tackle our housing crisis. Our government seem to be doing a lot on the demand-side of this market but maybe policies like this will help us to get the radical boost in housing supply that we need. These articles by Urban Kchoze and Konchi Value are great reads if you want to delve deeper into this topic.

Consuming saturated fat may not cause heart disease

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death worldwide. It is responsible for approximately 20% of all deaths in high-income countries and 40% of deaths in low and middle-income countries. One major cause of CVD is believed to be a diet which contains too much fat, specifically one which has high saturated fat intake. This theory is commonly referred to as the “cholesterol hypothesis”. It states that an overconsumption of saturated fat leads to high levels of cholesterol in your blood and this leads to the buildup of plaque on your artery walls (atherosclerosis) which increases your risk of heart disease. This theory dates back to studies done in the 1950s called the Seven Countries Study and the Framingham Heart Study and has been a long-held convention in medicine. As a result, medical associations across the world have been recommending people to limit their consumption of fat, particularly saturated fat for decades.

However, a study came out in the European Journal of Preventive Cardiology a few weeks ago which seemingly proves this theory wrong. The study’s results section states:

“Collectively, neither observational studies, prospective epidemiologic cohort studies, RCTs, systematic reviews and meta analyses have conclusively established a significant association between saturated fatty acids in the diet and subsequent cardiovascular risk and coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction or mortality nor a benefit of reducing dietary saturated fatty acids on cardiovascular disease risk, events and mortality. Beneficial effects of replacement of saturated fatty acids by polyunsaturated or monounsaturated fat or carbohydrates remain elusive.”

There has been a community within medicine making this argument for a while. One such example is a paper from 2008 called “the fallacies of the lipid hypothesis” (another name for the cholesterol hypothesis). Thinking about it from first principles, isn't it a bit strange that even if we have been consuming significant amounts of saturated fat in the form of meat for millions of years that we are now being asked to limit our consumption of it for health reasons? We don’t even need to look at our past to see flaws in this logic. There are still hunter-gatherer tribes around today like the Hadza people of Tanzania where 72% of the male diet is meat. They have been found to have very low incidences of heart disease and optimal levels of cardiovascular health biomarkers. Here is a good long read on the argument against the cholesterol hypothesis if you want to read more.

So what alternative theories do they put forward as the cause for heart disease? Some suggest that inflammatory biomarkers and insulin resistance (i.e. reduced ability to break down and absorb glucose) hold more clues in the quest to find out what causes heart disease. Some studies have shown some promise in this theory. This study found that in a cohort of women insulin resistance was 6 times more correlated with heart disease than LDL cholesterol, the compound that is said to be the link between saturated fat consumption and heart disease. This theory is also more compatible with the first principles reasoning I mentioned earlier. Regardless of where you stand on this one, it should be clear that the argument is not as clear cut as we are led to believe.

Some laughs to brighten your day

As always, here is some stupid internet content to make you laugh.

Note to readers: if something provably works and is contrary to mainstream thought, there is a good chance that Will's World would like to cover it, if you send me an idea like this I will buy you a pint or another beverage/snack of your choosing or send you the cash equivalent. You will of course also be credited in the newsletter if I choose to write about it.

NIMBY stands for "Not In My Backyard" and is used to describe individuals who do not want something new to be built (i.e. housing, new school, new road etc.) in their area. These people are typically in favour of strict land use regulations and lead/join local movements to prevent new developments being built. The collective force of NIMBYs have contributed to increased housing prices in many cities across the world.

Learned something new from your Japanese housing policy bit. Great analysis!